Now that the Medieval Londoners Project is 14 months old (we launched in June 2020), a regularly published blog seems to be a good way to alert users to new features of the website, especially new data in the Medieval Londoners Database (MLD for short). If you are interested in receiving these monthly posts, please click this link: Subscribe.

As of 5 August 2021, MLD has almost 20,000 records for 13,127 different Londoners who lived between c. 1100 and 1520. In recent months we have added :

- All London MPs from 1290 to 1558

- Southwark residents who paid the poll tax in 1381

- Southwark manorial officials

- Medieval Londoners who are the subject of articles in The Ricardian (especially women)

For other recent and forthcoming additions (including c. 4000 testators in the Husting wills and c. 9000 people mentioned in the Coroners’ Rolls), see What’s New in MLD.

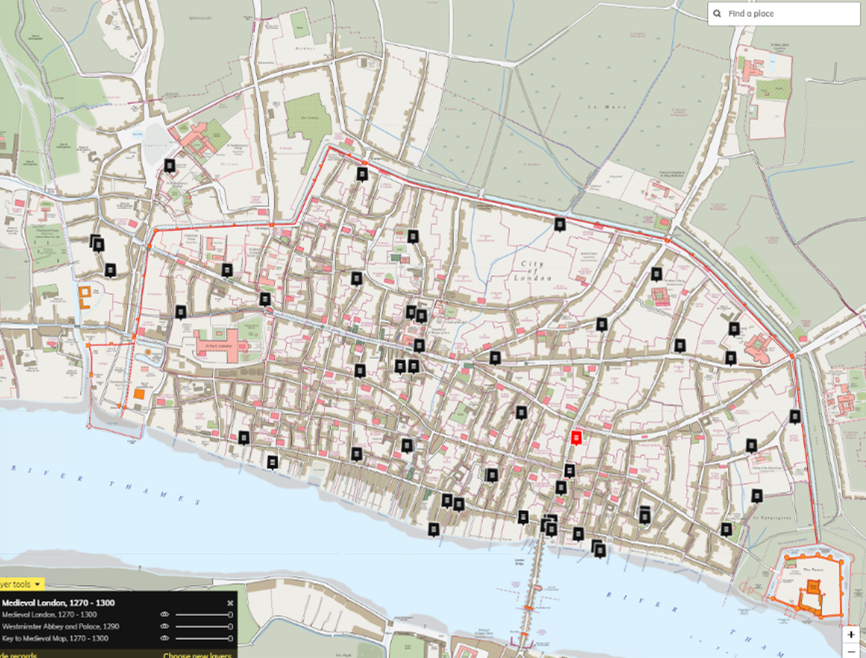

MLD and Layers of London

In addition to providing content of value to students, scholars, and the general public, one of the main aims of MLD is to offer opportunities for digital training and experience. For example, a digital assignment for a course on Medieval London at Fordham University required students to structure information about the parties to a medieval deed using the MLD data entry spreadsheet, then map the property in the deed on the Layers of London mapping platform, and finally provide hyperlinks to the deed parties who were already in MLD. In turn, MLD records of these deeds allow users to link to the Layers of London record for that property. See the Layers collections named Medieval Londoners and Medieval Londoners 2 for examples of the students’ work . For detailed instructions and resources needed for the assignment, see Digital Pedagogy: Medieval Londoners Mapping Project.

Portraits of London Aldermen

Simon Eyre, Draper: Alderman, Sheriff, and Mayor of London. MLD Person ID 264. Image copyright London Picture Archive, London Metropolitan Archives.

Another project undertaken by students is a new website called Visual Sources of Medieval London, which offers a a curated guide to medieval and modern paintings that depict (1) medieval Londoners and their surroundings, (2) early modern engravings of medieval buildings before the Great Fire, (3) modern drawings that reconstruct medieval structures from archaeological evidence, and (5) seals owned by medieval Londoners and their civic and religious institutions. The work is done largely by undergraduates who are awarded a Digital Historical Images Internship to do research on a specific group of images and learn how to enter metadata on the OmekaS platform. Check out, for example, the Portraits of London Civic Officers collection, a group of 25 pen, ink, and watercolor drawings done c. 1446-47 by Roger Leigh, Clarenceux king of arms. The collection features a short but fully referenced essay about the portraits, full metadata about each portrait, and a high-quality downloadable image, thanks to permission granted by the London Picture Archive of London Metropolitan Archives, which owns and holds copyright of the images.

Recent Scholarship on Medieval London

Charlotte Berry, “Guilds, Immigration, and Immigrant Economic Organization: Alien Goldsmiths in London, 1480–1540,” Journal of British Studies 60:3 (2021): 534 – 562

Immigration was essential to trades reliant on fashion and high skill in London around the turn of the sixteenth century. This article explores the patterns of migration to the city by continental goldsmiths between 1480 and 1540 and the structure of the communities they formed. It argues that attitudes to migration within the London Goldsmiths’ Company, which governed the trade, were complex and shifted in response to evolving national legislation. A social network analysis of the relationships between alien masters and servants indicates how the alien community changed and adapted. Taking a view across the traditional late medieval and early modern period boundary allows for a deeper understanding of how attitudes to migration and to migrant communities changed as London’s population began to grow (abstract from JBS). DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2021.2

Katherine L. French, Household Goods and Good Households in Late Medieval London

Consumption and Domesticity After the Plague, University of Pennsylvania Press, August 2021.

In the long aftermath of the Black Death, wages in London rose in response to labor shortages, many survivors moved into larger quarters in the depopulated city, and people in general spent more money on food, clothing, and household furnishings than they had before. This book looks at how this increased consumption reconfigured long-held gender roles and changed the domestic lives of London’s merchants and artisans for years to come. Drawng on surviving household artifacts and extensive archival research, Prof. French examines how changes in material circumstance reshaped domestic hierarchies and produced new routines and expectations. Recognizing that the greater number of possessions required a different kind of management and care, French puts housework and gender at the center of her study. Historically, the task of managing bodies and things and the dirt and chaos they create has been unproblematically defined as women’s work. Housework, however, is neither timeless nor ahistorical, and French traces a major shift in women’s household responsibilities to the arrival and gendering of new possessions and the creation of new household spaces in the decades after the plague (from the publisher’s website).