Welcome to the September 2022 posting of the Medieval Londoners Blog. Please subscribe to receive updates on new material added to the Medieval Londoners Project and other items of interest to those working on medieval London. Since our last post, Medieval Londoners has added a new page on London Family Trees, and we have uploaded three new datasets to MLD: all of the merchant biographies compiled by Sylvia Thrupp, records dealing with embroiderers and their associates, and records dealing with properties: mostly deeds, but also c. 80 entries from the 1461-2 rental of London Bridge. To see the datasets we plan to upload in the coming months, see What’s New in MLD?

Sylvia Thrupp’s Merchant Biographies

Scholars of medieval London have long mined the some 400 biographies compiled by Sylvia Thrupp for her classic book, The Merchant Class of Medieval London, c. 1300-1500 (Ann Arbor, 1948). With the help of Frances Eshleman, the full text of Thrupp’s biographies are now available in MLD. This is the third set of records that we have culled from Thrupp’s work. Two years ago, we included her list of London taxpayers in 1436 (appendix B in The Merchant Class) and the names of masters and clerks of the Bakers in Appendix III of her A Short History of the Worshipful of Bakers of London (Croydon, 1933). Other important works on London by Thrupp include “The Grocers of London, a Study of Distributive Trade,” Studies in English Trade in the 15th Century, ed. E. Power and M. M. Postan (London, 1933); and “Aliens in and around London in the 15th Century,” Studies in London History Presented to P.E.Jones, ed. A.E.J. Hollaender and W. Kellaway (London: Hodder, 1969).

Thrupp was born in Surrey in 1903 but grew up in Canada from the age of five. She received her BA and MA from the University of British Columbia, and after teaching high school for two years, moved to England to study at the University of London, where she received her Ph.D. in 1931 and stayed until 1935 as a post-doctoral researcher. After teaching at the University of British Columbia (1935-1944) and the University of Chicago (1945 to 1968), she was named to the newly established Alice Freeman Palmer Chair at the University Michigan. In 1958 she founded the journal, Comparative Studies in Society and History, in 1973-4 she served as president of the Economic History Association, and in 1981 she received the AHA’s Award for Scholarly Distinction. Well after her retirement from Michigan she moved to Princeton when she married a fellow medievalist, Joseph Strayer, and after he died, moved to California, where she passed away in 1997.

For full details on Thrupp’s career and scholarship, see the 2006 issue of Medieval Feminist Forum, which drew on papers given at a session on Thrupp at the 2004 meeting of the Medieval Academy of America. It includes articles by Caroline Barron on “The Making of an Early Social Historian;” Joel Rosenthal on “The Chicago Years 1946-61;” Barbara A. Hanawalt, “Feminism? If I Made It, So Can You,” and Michelle M. Sauer “Finding Syvlia Thrupp.”

The Embroiderers

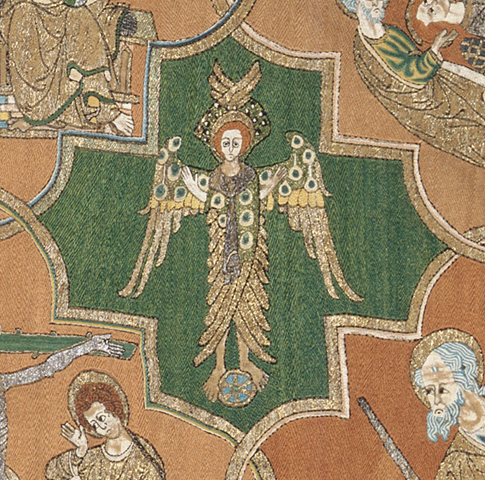

A type of English embroidery called opus anglicanum achieved international renown in the high middle ages. Usually employed in church vestments, this elegant embroidery used rich materials like damask and velvet fabrics, gold and silver thread, and precious or semiprecious stones. Embroiderers added decorations and designs to an otherwise finished piece of cloth, such as church copes, orphries, and chasubles. Gold thread was carefully sewn by embroiderers into the design to catch the light using the couching technique, as illustrated in the fourteenth-century Syon Cope, which can be explored in detail here.

Some of the most well-known and accomplished embroiders worked for the royal household. Henry III, for example, commissioned Mabel of Bury St Edmunds at least twenty-four times. She created a chasuble and orphrey that Henry later requested to have ornamented with pearls and gold. These vestments were completed only after other embroiderers appraised and approved her work. She last appeared in 1256 when the king gifted Mabel a rabbit fur for her service. In later centuries, Queen Philipa and Elizabeth of York ordered bedspreads that required large teams of embroiderers and designers that were headed by a chief embroiderer.

A dataset with 180 records referring to professional embroiderers in London and another 140 records of Londoners associated with these embroiderers (such as their spouses, children, and business associates) was recently uploaded to MLD. The dataset draws on printed collections, including the Plea and Memoranda Rolls, Letter-Books, and Calendars of Close and Patent Rolls, among other sources. One of the earliest entries is from 1244, when Henry III commissioned Edward Fitz Odo to create a red silk dragon embroidered with gold and a tongue that “should be made to resemble burning fire and appear to be continually moving.” The majority of the records, however, are from the fifteenth century when the embroiderers became a recognized Lesser Mistery, called the Broiderers.

Foreign expertise is also evident in the craft. There were six alien embroiderers residing in Southwark in 1436: two from the Netherlands, two from Austria, and two from France (Liege and Picardy. In the mid fifteenth-century alien subsidies, four other German and Dutch embroiderers were recorded, two in Cripplegate ward, and one each in Castle and Cheap wards. In 1444, the Dutch embroiderer William Outcamp, who resided in Southwark, formally became a denizen of England.

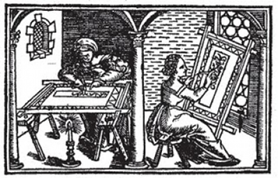

The dataset is predominantly male, except for one female apprentice, Alice Catour, and a few known female royal embroiderers like Mabel. The data are likely skewed because female embroiderers often operated under different occupations, such as seamstress and silkwoman, who specialized in decorating fine linen, or they were servants in the households of embroiderers who took on some craft work. Women embroiderers in the workshops often conducted specific tasks, such as lining, trimming, and mounting, as illustrated in the woodcuts below from an early sixteenth-century pattern book, showing women transferring embroidery designs (Alessandro Paganino, Il Burato, Libro de Recami (1518, from 1527 reprint), Leiden, Textile Research Center).

Embroiderers worked closely with other cloth trades, particularly tailors, haberdashers, mercers, and drapers. These working relationships could cause confusion. In 1395 foreigners William Tiller and Terry Drypsteyn requested translation to the Broiderers after they mistakenly entered the Tailors craft. Embroiderers also provided social and professional security to others within and without their craft. In 1364 John Hyndale mainperned to protect the goods of the tailor Richard Pecock. In 1496 John Maidenwell entered into a bond with a pewterer, a butcher, and a grocer to provide for the three girls of the deceased John Uttersall, a stationer. A small number of embroiderers also took part in civic governance. Robert Ashcombe, for example, served as the Broiderers’ representative on the common council and later as a representative for Cripplegate. While employed as the king’s embroiderer (1396-99), Ashcombe was elected as a MP for London and also served as an auditor for the city. The expertise of embroiderers was also recognized by other crafts, as when John Daunde, as a warden and master of the Mistery, testified on the condition of silk in a skinner’s complaint against a Florentine merchant.

-Morgan McMinn

London Family Trees

In addition to providing biographies of individual merchants, Sylvia Thrupp also sketched out three family trees in a narrative format. She is only one of the scholars and family historians who have created a wide range of useful family trees and histories about individual kin groups in medieval London. We have attempted to disambiguate this material for entry into MLD, but have now created a London Family Trees page to provide links to the full family histories so that users can see the material as presented by the original compilers. These family trees come in a variety of formats, but are usually diagrams showing kinship ties through marriage and progeny. The family trees noted below include redrawn and newly drawn diagrams, as well as copies of the original family trees when we have permission to reproduce them. We welcome contributions of other family trees or histories that cover the period c. 1100 to 1520 for those residing in London, Southwark, or Westminster; please use the contact form to send us the material or the link.

Family of Abigail of London (from Hillaby, Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History)

Cely/Sely family (from Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London)

Frowick/Frowyk family (from Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London)

Gisors/Gisorz, Jesors family (from Thrupp, Merchant Class of Medieval London)

L’Eveske family (from Hillaby, Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History)

Family of Leo I le Blund (from Hillaby, Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History)

Family of Master Moses of London (from Hillaby, Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History)

Family of Rabbi Josce (from Hillaby, Dictionary of Medieval Anglo-Jewish History)

Shordych family (compiled by M. Kowaleski)

Tate family of St Dunstan in the East parish (from Sutton, A Merchant Family… The Tates

Tate family of All Hallows Barking parish (from Sutton, A Merchant Family… The Tates)

Tate family of St Dionis Backchurch parish and St Anthony’s Hospital (from Sutton, A Merchant Family… The Tates)

Search Tips for MLD—or How to Find Girdles and Hermits

MLD’s Search for Londoners page lists four different ways to search the database. Most users go straight to the Browse Londoners or Browse Records options, both of which allow you to search on names or a whole other range of fields, some of them conveniently filtered on the right-hand pane. But these options only allow you to find Londoners for whom we have made a separate record. It is important to know that MLD does not make a separate record for each person named in all records (particularly wills); to do so would unduly lengthen the time needed for data entry as well as the space reserved for records on the MLD platform. For deeds, for example, we often omit the names of witnesses. So the quickest way to find these individuals is to enter their name in the white text box above the Activity field in the Browse Records screen, which will find all names mentioned in the master record, not just those for whom we have made a separate record.

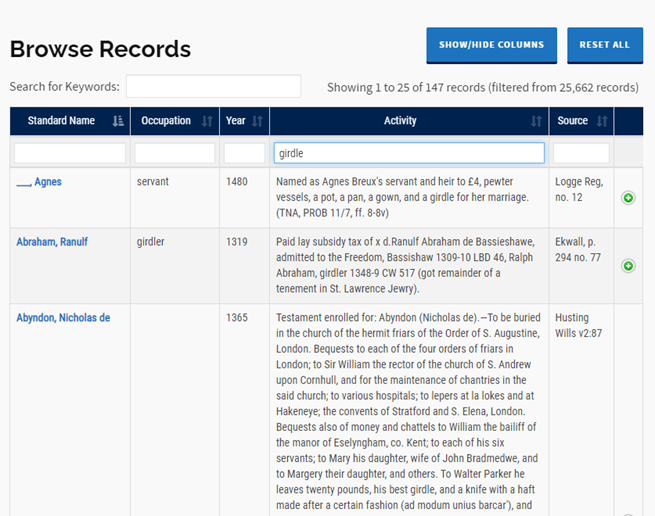

But searching on the Activity field can also be used to look for types of people (like hermits) or things (like girdles). Placing the word ‘hermit’ in the white box above the Activity column yields 23 records, most of them bequests to hermits. Placing ‘girdle’ in this box produces 147 records from a variety of sources, as noted in the screenshot below.

Users can also search the Activity field with words like ‘dower’ (272 records) or ‘jewel’ (81 records) or ‘quitclaim’ (84 records). But there are limits to this type of search. For example, a search on ‘rape’ brings up 25 records, but they mostly include references to drapers because the search just looks for the string of letters in the word, not the word by itself. Similarly, the search on ‘girdle’ also brings up records with ‘girdler’ in the Activity field.

New Publications on Medieval London

Records of the Jesus Guild in St Paul’s Cathedral, c. 1450-1550. An Edition of Oxford, Bodleian Ms Tanner 221, and Associated Material, ed. Elizabeth A. New, London Record Society 56 (Woodbridge: Boydell, 2022). Prints the extant records of the fraternity of the Holy Name, known as the Jesus Guild, which was based in the crypt of St Paul’s cathedral. Founded in the mid-fifteenth century, the guild was re-organised in 1506 after problems involving the misuse of funds. Accompanied by a thorough introduction, this edition prints (1) licences, two sets ordinances (the earliest is dated 1506 ) and letters of protection gramted to the Guild and (2) the Guild’s annual accounts from 1514/15 to 1534/5. The bulk of the Guild’s income came from farming out its right to collect membership fees and donations for prayers and pardons (indulgences). Expenses were more varied and included the costs of its lavish liturgical celebrations and work on the Jesus Chapel. The appendices contain the 1555 inventory of St Faith’s church, which included items that may have belonged to the adjoining Jesus Chapel, and short biographies of the guild wardens in this period. The text is in Middle English, with a select glossary.

Marcus Meer, “Heraldry, Corporate Identity, and the Battle for Symbolic Capital in Late Medieval London,” The London Journal (Aug. 2022)DOI: 10.1080/03058034.2022.2059232. Abstract: This article analyzes grants of arms obtained by London guilds between 1439 and 1530 to argue that corporate heraldry was not just a convenient means of identification but was meant to be seen as a semantically dense visual communication of corporate identity. The heraldic signs conferred by such grants, confirmations, and augmentations of arms served as official acknowledgments and visual representations of their recipients’ symbolic capital of honour. By prominently displaying corporate arms on central stages of corporate self-representation such as halls, churches, and rituals, guilds reinforced the connection between heraldry, identity, and corporate honour. This proud heraldic display of corporate identity, just like the pursuit of grants of arms, reflected a need for weapons in an intensifying battle for symbolic capital that the guilds of late medieval London faced, perhaps as a result of economic difficulties that marked the later fifteenth century.

David Mason, “The Role of London’s Urban Foundation Legends in Late-Medieval Historical and Political Cultures,” The London Journal (Feb. 2022). DOI: 10.1080/03058034.2022.2028451. Abstract: In 1442, the authorities of London issued a formal prohibition against the spread of a lie that the first and best mayor of London was a cordwainer (shoemaker) named Walsh. This article investigates the context for this story by examining contemporary uses of foundation narratives for important institutions of London life, including the city, corporation and mayoralty. These foundation legends grew from a distinctive urban ‘historical culture’. This article argues that historical culture and foundation legends were important means of cultivating cultural prestige, defining the purposes of institutions, discussing the power relationships between different political institutions and engaging in political communication. By comparing the ‘Walsh’ legend to other variants of the London mayoral origin story, we can discern contemporary political debates about the purpose, powers and political control of key institutions in London life.