Welcome to the second posting of the Medieval Londoners Blog. Please subscribe to receive updates on new material added to the Medieval Londoners Project and other items of interest to those working on medieval London. Since our last post, MLD has added the full text of the 3,908 Husting Court wills and 112 deeds from A Descriptive Catalogue of Ancient Deeds in the Public Record Office, ed. H. C. Maxwell-Lyte, 6 vols. (London, 1890-1915). Currently being processing for upload are 900 records of London Goldsmiths, including Wardens and Renters of the craft from 1335 to 1510, and biographical notes of prominent Goldsmiths, taken from T. F. Reddaway, The Early History of the Goldsmiths’ Company, 1327-1509 (London, 1975). For other datasets, see What’s New In MLD?

Husting Court Wills Now in the Medieval Londoners Database (MLD)

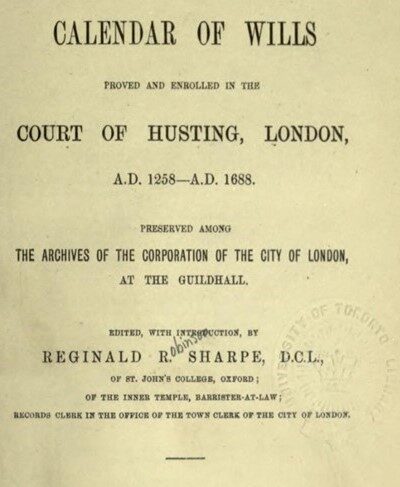

Many London citizens (those who belonged to the freedom of the city) enrolled their wills in the Court of Husting. These wills are copies that primarily record rents and tenements in the city, so they rarely include a testator’s properties outside of London, nor the full bequests of chattels or personal goods. Nonetheless, the Husting wills offer significant details about the wealth, status, occupation, craft affiliations, families, and colleagues of the 3,473 men and 435 women whose wills were enrolled in 1258-1578.

The original Latin text of these Hustings wills was translated and summarized in a calendar published in two parts by R. R. Sharpe, Calendar of the Wills Proved and Enrolled in the Court of Husting, London (London, 1889-90). Thanks to the efforts of Dr Liz Duchovni, the full content of the calendar of 3,908 wills for 1258-1578 have now been structured and placed in MLD under the name of the testators. Sharpe’s text includes all names and bequests, but he sometimes summarized descriptions of property bequests in the later wills, which tend to be far longer than the earlier wills. The text of all wills and their footnotes have been reproduced exactly as in the print text, though we worked originally from the XML of the British History Online text, except for 8 entries on pp. 589-94 and some scattered footnotes, which had been inadvertently left out of the BHO online version.

Testators who used this court were generally well-off Londoners who owned property in the city. Given the large number and many details included in the wills, we have not made MLD entries for individual beneficiaries noted by the testators, although it is possible to find their names by searching on the Activity fields, using any of the three search functions in MLD.

We are now working on including in MLD a list of 2,350 wills and inventories of those living in London, Southwark, or Westminster up to 1540 that were enrolled in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (now in The National Archives).

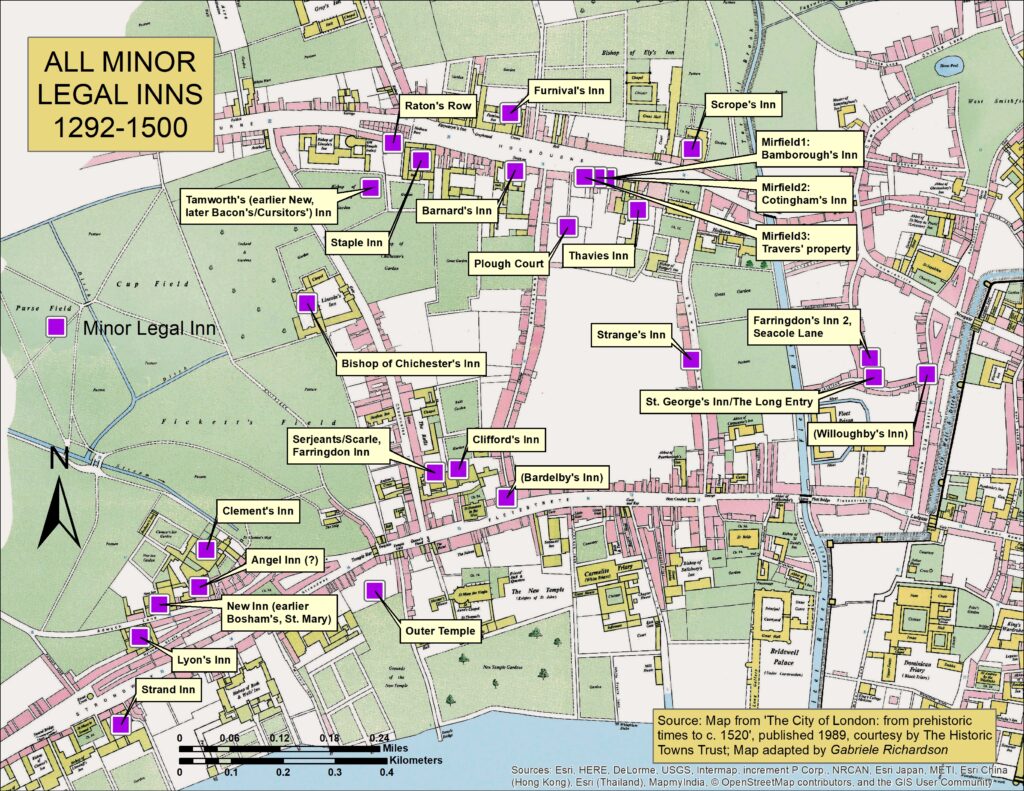

Maps of the Common Law Inns in Medieval London

Thanks to the work of Malcolm Richardson (text) and Gabriele Richardson (cartography), maps are now available of the changing location of London’s “legal inns,” which provided legal training and a residence for men pursuing careers in the common law courts. There were two types of legal inns: (1) the “major” Inns of Court (including Lincoln’s and Gray’s Inns, and the Inner and Middle Temple), and (2) the “minor” Inns of Chancery, which through the seventeenth century were preparatory for the major Inns of Court.

Common law was based not on written laws but on case law, that is, rules made by judges. This focus on legal precedents meant that students were trained by observing and taking notes of the judges’ discussions at the royal courts at Westminster and then staging disputations (moots) and mock trials and attending lectures (readings) in the legal inns when the courts were not in session. Even practicing lawyers attended the courts as part of “continuing education,” and annually collected notes about trials, called “Year Books,” which were widely circulated among lawyers. Although legal training in the UK now occurs in universities, the Inns of Court continue to serve as the major credentialing agencies for barristers (trial lawyers).

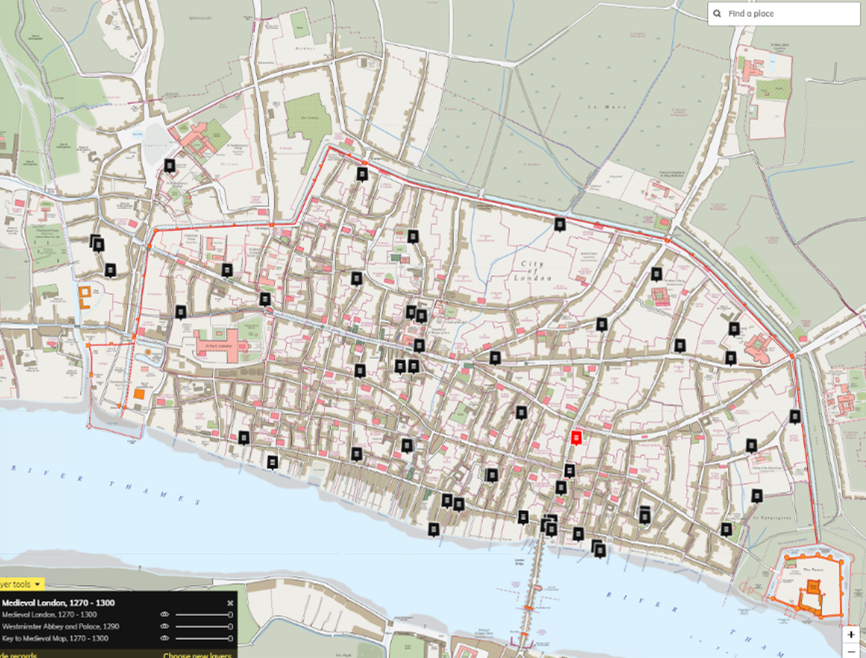

The series of maps published here illustrate the location of legal inns in London at several points in their history from about 1292 to the end of the fifteenth century. Clustered in London’s Holborn district, Fleet Street, and the Strand, the legal quarter then and now was situated just outside the city walls. Holborn was also home to the Chancery, an important royal office which authorized and produced by hand voluminous official documents in the king’s name. The maps focus on the locations of the “minor” Inns of Chancery, since the four “major” Inns of Court have remained at the same locations since 1422.

After a general introduction to the history of the legal inns in medieval London, the site provides links and explanatory text about six maps, including the location of the earliest inns (Map A) and a summary map of all legal inns up to 1500 (Map C). Two maps illustrate the investment of Chancery clerks (many of relatively low status) in shops, dwellings, and inns in Holborn after the Black Death up to c. 1425 (Map D); thereafter these investments virtually stopped (Map E). The location and names of the inns as they were in 1470, when Sir John Fortescue, Chief Justice of the King’s Bench, famously described them are illustrated in Map F. Another nineteen maps are available upon writing to Prof. Richardson.

The maps, which can also be downloaded as high-quality 1200 dpi images, are based on the map from The City of London from Prehistoric Times to c. 1520, edited by Mary D. Lobel (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989). The Tudor-era map used here was created by Col. Henry Johns. It has since been revised by Caroline Barron, Vanessa Harding, and others and published by the Historic Towns Trust in 2018; The City of London from Prehistoric Times to c. 1520.

For biographical information on the clerks of Chancery, see Malcolm Richardson, The Medieval Chancery under Henry V, List and Index Society Special Series vol. 30 (London, 1998). We hope to add these data to MLD in the near future.

New Book on Medieval London

The London Jubilee Book, 1376-1387. An Edition of Trinity College Cambridge MS O.3.11, folios 133-157. Ed. Caroline M. Barron and Laura Wright. London Record Society, Boydell and Brewer, 2021. The so-called ‘Jubilee Book,’ long believed lost, was a collection of reforming measures produced by a committee of leading London citizens set up to examine civic ordinances in 1376, the jubilee year of Edward III’s reign. The reforms caused so many controversies and disputes that in 1387 the Jubilee Book was publicly burnt. This volume prints the original text and translation of a fifteenth-century copy of the ‘Jubilee Book’ that most likely represents an early draft. It is accompanied by two introductory essays: one by Caroline Barron that discusses the dating and scribe and contextualizes the reform measures in the Book, and a second by Laura Wright analyzing the language of the manuscript.

New Digital Project: Living and Dying in Late Medieval London

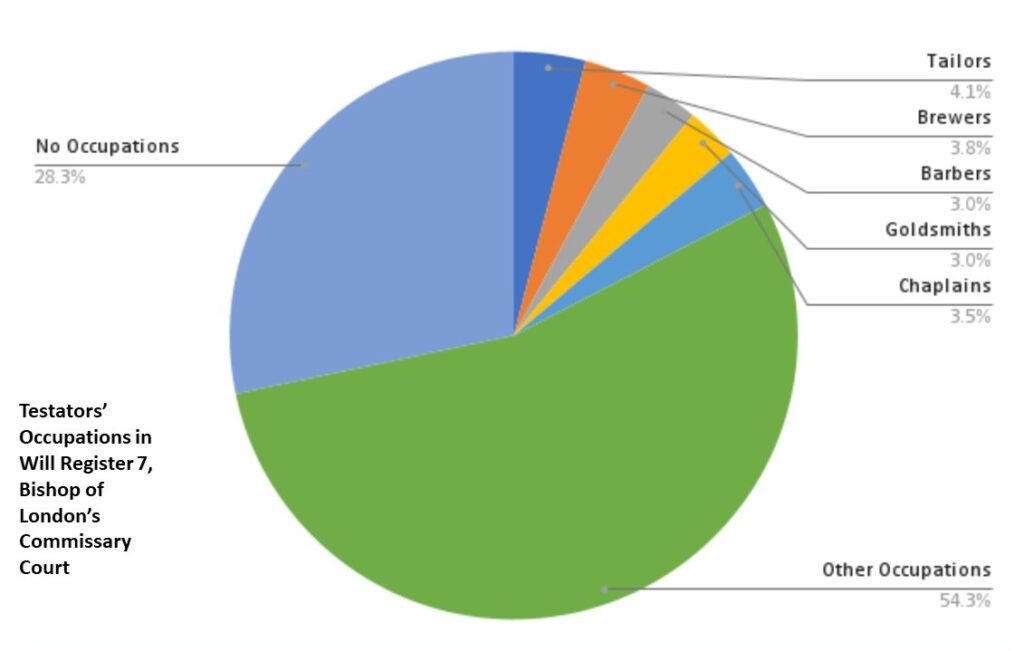

“Living and Dying in Late Medieval London: Stories from Register 7 of the Commissary Court” is a digital project put together by six students in the History Lab class of Prof. Katherine French at the University of Michigan in the Fall 2021 semester. The project focused on 368 wills in Register 7 (covering 368 wills, 80 per cent from Londoners and most of them dating to 1484-89) of the Bishop of London’s Commissary Court, which was digitized by the London Metropolitan Archives. Using the Story Maps digital platform, the students focused on 41 wills from nine Grocers and from the two parishes of St Sepulchre without Newgate and St Magnus Martyr. The students also looked closely at the occupations and immigrant status of these testators, as well as their bequests of household goods. For more details on the student assignments involved in the course, see the Pedagogy page of Medieval Londoners

Talks on Medieval London at the NACBS conference

The annual meeting of the North American Conference on British Studies occurred in Atlanta, November 10-14, 2021. There were four medieval sessions, which included the following papers focusing on medieval London.

“Women, Seals, and Identity in Thirteenth-Century London.” John McEwan, St. Louis University

“Marrying Up or Down? Marital Patterns among Mercantile Families in Late Medieval London.” Grace Campagna, Fordham University

“A House in the Country: London’s Merchants and their Houses.” Katherine L. French, University of Michigan

“The Rise of Inns in Medieval London: Sources and Evidence.” Martha Carlin, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee

“New Perspectives on the Medieval London Port Customs Accounts.” Maryanne Kowaleski, Fordham University

“The London Jubilee Book 1376-1387: Lost and Found.” Caroline Barron, Royal Holloway and Bedford New College